On January 2, 1985, my father wrote his Living Will – it was his 66th birthday. Always being prepared, he drew it up in his own handwriting to spell out his final wishes just in case he could no longer take part in life-death decisions for his own future. It was his wish to die naturally (and honorably) like a true samurai

Contained on the second page, was a verse – simple, but elegant. Upon closer examination, I concluded that it was a jisei (辞世), or in the words of Zen Buddhist scholar, D.T. Suzuki, a “parting-with-life verse.” Westerners have come to know it as a “death poem.” He wrote: “Cherry blossom fall when the time is right. I too will fall when it is time to go.”

The idea of my father writing such a verse left me dumbfounded. In all honesty, I didn’t think he was even capable of authoring such polished poetry.

I studied the poem’s words to determine what his thoughts were when he wrote it to uncover its underlying message. It didn’t immediately reveal itself to me, until now.

The poem itself is simplistic and focused. It’s rooted in Zen Buddhism, yet it’s also aesthetically elegant (fūryū); his words are heartfelt and overpoweringly sorrowful (mono no aware). The poem stirs up intense emotions and, yet, it’s intimacy, and profoundness has much philosophical appeal. As a result, it inspired me to learn more about this ancient custom of jisei in my effort to reveal the poem’s symbolism and meaning and even connect me with my father’s soul.

On his 66th birthday, father handwrote his Living Will on a couple of pages from a Mead composition notebook. On these pages, now yellowed by time, he declared his dying wishes. Curiously, on the second page, an innocent four-line verse was written within its top margin as if it were added as a postscript.

Cherry blossoms fall

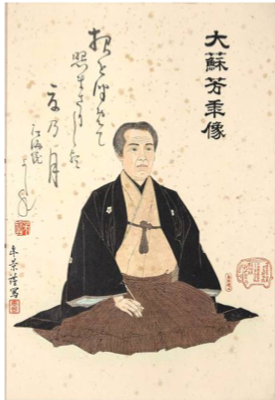

Roy Isami Ebata (1919-1990)

when the time is right

I too

will fall

when it is time to go

The poem didn’t seem to fit any traditional Japanese poetic forms like haiku or tanka (formerly called waka). It has highly regimented metrics, and it places a lot of demands on intuition and strict discipline of structure, content, restraint, and subtlety.

Instead, my father’s poem seemed to stray toward a more contemporary and freer style of Japanese poetry. It was much influenced by new forms of Western poetic forms introduced during post-war Japan. This modern poetry is called gendai-shi (現代詩). It translates as “contemporary poetry,” with looser metrics and regarded as a form without boundaries. The verse is freer and with fewer rules such as fixed syllable numerations per line or fixed set of lines.[1]

That said, his poem seemed contrary to his character. The one thing I remember most about father was his commanding nature. His rigidness and stoicism – he had the discipline for suppressing and concealing his emotions and feelings – and combined with his authoritarian ways, made him (perhaps) too strict for the times. He was a chōnan (長男) or eldest son, so he was difficult to please or gain his approval because of his high standards and high expectations for his own children. His words were final, right or wrong, and he didn’t like to hear excuses. He didn’t show much physical or verbal affection, probably because he didn’t know how to express it outwardly. So, I was dumbfounded by the idea of him writing such a refined and freer style of poetry. But he may have found his only pressure release valve through poetic verse

Five-years later, my father was hospitalized with stomach cancer and admitted to Kuakini Medical Center in Honolulu.[2] But, he eventually died from heart failure; he was only 71 years old.[3]

While hospitalized, my father summoned his younger brothers to the hospital before he went into surgery the following day. My father asked them because he wanted to discuss his final wishes should he not make it through surgery.

Death is as much a reality as birth, growth, maturity

Roy Isami Ebata, Living Will (January 2, 1985)

and old age—it is the certainty. I do not fear death

as much as I fear the indignity of deterioration,

dependence and hopeless pain.

In his Living Will, my father stated the condition for which he wished to die: “[If] there is no reasonable expectation of my recovery from physical or mental disability…that I be allowed to die and not be kept alive by artificial or heroic measures…I ask that you all will let me die a natural death like a true samurai.”[4]

He must have written his jisei and chosen the symbolism and meaning of falling cherry blossoms to portray his desired death

A FATHER’S DYING WISHES

My father, Isami Ebata, as he was known during the war. He adopted the American name “Roy” in 1962 and became known as “Roy Isami Ebata.”

My eldest brother was working on preparations for our father’s Buddhist funeral service at Hosoi Garden Mortuary in Honolulu. That’s when my uncles contacted him to relay our father’s final wishes.

After a Buddhist funeral service, father was to be interred at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific at Punchbowl in Honolulu, so one of his last wishes was to have his gravestone marker bear the Dharma Wheel, which has universally become the symbol for Buddhism.[5]

My father lived in Pa’auilo on the Big Island of Hawai’i until he was 24 when he enlisted in the US Army on February 23, 1942, with the rank of private. He was stationed at Schofield Barracks on the Island of O’ahu, Hawai’i. On his enlistment papers, he indicated his religious affiliation was “Protestant” to conceal the fact that he was a Buddhist and avoid any association with Japan.

Although my father was born and raised as a Buddhist, I don’t think he was a practicing Buddhist during his married life. He didn’t belong to a Buddhist temple or attend Obon (お盆) to honor our dead ancestors. There wasn’t any butsudan (仏壇) or Buddhist altar in our home. The only Buddhist custom he observed was the oshōgatsu (お正月) or Japanese New Years. None of his children were raised as Buddhists, either. Instead, we were sent to Sunday school at Makiki Christian Church in Honolulu.

But even though he wasn’t a practicing Buddhist, his religious connection must have been important after being honorably discharged 45-years later. He wanted to have his Buddhist affiliation permanently noted on his gravestone marker. In Japan, there’s a common saying: “Born Shinto, die Buddhist.” My father must have believed this saying, as well.

I ask that you all will let me die a natural death

Roy Isami Ebata, Living Will (January 2, 1985)

like a true samurai.

My father’s other wish was to have one of his younger brothers recite the poem that he had written on his Living Will at his Buddhist funeral service. This was the first time I heard his verse.

Listening to the verse being delivered by one of his brothers: “Cherry blossoms fall when the time is right…”

I felt deeply moved as my teary eyes overflowed into a slow trickle down my cheeks. At the time, I had no idea that my father’s poem wasn’t an ordinary poem, but it resonated profoundly with me. I later discovered that the verse was known as a jisei no ku (辞世の句), or just jisei (辞世). Westerners came to know such poems popularly as “death poetry” in the Pacific War during World War II.

Before their deaths, the samurai wrote jisei. It describes the ancient Japanese custom of composing a “parting-with-life verse” in the words of D.T. Suzuki (1870-1966), a scholar of Zen Buddhism. Jisei is characterized by the concept of fūryū (風流), an appreciation of nature amid tragedy and death.[6] Such death poems try to express as vividly as possible the sentiments of the person in the face of death.

I came across a jisei that seemed like my father’s, except it involves the ume or plum blossoms. This jisei was written by the haiku poet, Baiko, who died in 1903 during the Meiji period at age 60:

Chiru ume ni

miaguru sora no

tsuki kiyoshi

Plum petals falling

I look up—the sky,

a clear crisp moon.

Baiko’s jisei refers to the “plum petals.” It suggests the season of early spring when it’s still cold in Japan. Their “falling” represents both death and the transient nature of life, a concept central to Zen Buddhism. He references seeing the “moon,” which can represent enlightenment and reinforced by the moon being “clear” and “crisp.” Baiko’s jisei offers a hint of the time and place of his final hours before his death. But also, it also gives a sign of his most intimate feelings, as if he made his peace with the world and hopeful in leaving it.[7]

The jisei is written simply but with great philosophical appeal and with a sincere appreciation of nature. It reminds one of the life-death connections between Zen Buddhism and Shinto.

Baiko’s poem also contains a peaceful sense of calm, dignity, and gratitude (kansha 感謝) for life. He shares an experience so personal and private yet familiar, but I also sense comfort and self-assurance in the face of a natural phenomenon that many Westerners fear so much.

For some strange reason, even though more than two decades had passed since my father’s death, I kept thinking about his jisei and wondered why I felt so connected to it. I didn’t realize it at the time, but a jisei attempts to connect the reader with the author’s thoughts at the end. So, I pondered what my father’s feelings were at the time he wrote his jisei? He naturally accepted the fact that he would one day come face-to-face with death. He wasn’t afraid of dying, so what would be the spiritual legacy he wanted to pass on?

Like a samurai, my father intended to utilize his jisei to communicate his legacy. I wish there had been a cipher to decode any underlying message within the jisei. I pondered if the jisei was a “key” to enabling me to peer into his soul and reveal his true self. But to do this, I needed to understand the custom and art of jisei – without such critical knowledge, it would be challenging to interpret it. I felt that through his jisei, he was inviting me to investigate his soul to get to know him.

Fascinated by this ancient Japanese custom, I started questioning how well I knew my father. I thought I knew him, but he was more cultured of a man than I thought, or he had led us to believe about him.

Little did I foresee that efforts to understand my father’s jisei would lead me to a totally surprising moment while on a trip to San Francisco. It was a trip that would lead me to experience my first hanami (花見) or cherry blossom viewing. That moment turned into the most spiritual experience of my life. It was a moment my consciousness of the interrelationship between me, my father, and the cherry trees transcended to a higher level of understanding. It left me filled with love and peace for my father. (See “Hanami” posted on January 7, 2018.)

IMMIGRANT VALUES

My late father was stereotypical for a man born of his Nisei (second) generation. He was instilled with values by his immigrant parents that provided a strong foundation to succeed in life. Such values involved gaman 我慢 (quiet endurance), shikata ga nai 仕方がない (acceptance with resignation), and gisei (sacrifice). But these same values can have negative connotations as well.

Gaman (“Quiet Endurance”)

The characteristic that was utmost about my father was his stoicism and his discipline for suppressing and concealing his emotions and feelings. It sounds stereotypical of men of his generation. Still, he was a difficult person to “read.” His face was difficult to read or discern how he was feeling. He rarely complained and kept his emotions tucked away inside him. The Japanese call this gaman (我慢), which is defined as a kind of stoicism, a “quiet endurance.”[8] The term translates as “perseverance,” “patience,” “tolerance,” and “self-denial.”

Gaman taught my father to accept or to do one’s best in dealing with life’s adversities or in troubled times. A related term for gaman is the term gamanzuyoi (我慢強い), a compound with the word tsuyoi (強い), which means “strong” and “resilient.”[9] The term translates as “(very) patient” and “perseverance.” In other words, gamanzuyoi refers to “suffering the unbearable” or having the high capacity for a quiet and calm endurance. But it also meant having to maintain one’s self-control and discipline to endure the unbearable with patience and dignity.

To my father’s generation, a man who showed his emotions on his face was considered weak; a man didn’t show that he was hurting. I’m reminded of a scene from the 1999 movie Snow Falls on Ceda. In the movie, 8-year-old Nisei, Kazuo Miyamoto, is practicing kendō with his Issei father, Zenichi, whose character embodies traditional Japanese values. Zenichi strikes a blow with his shinai, a kendo sword made of bamboo, and Kazuo repels the blow.[10] Zenichi’s face – if he’s impressed – doesn’t show it. Kazuo lashes back fiercely, but Zenichi blocks each strike with ease. Zenichi then strikes Kazuo hard, flinging him to the ground. Kazuo bounces back up, snatching his shinai into the ready position, his face scrunched in pain. “Kazuo,” Zenichi yells out. “Never show your pain. Don’t ever show your feelings. On your face. Or anywhere.”

Displaying gaman was a sign of maturity and strength of character. My father used to tell me to keep your private matters private. He’d say don’t complain and keep your problems to yourself, as others may be worse off and have bigger issues than you. Maintaining silence was a way to demonstrate strength and politeness to others. Interestingly, the word jisei when it’s written using the characters 自省 translates as “self-control” and “self-restraint.” I suppose it could be the reasoning my father hid the fact that he was suffering from stomach cancer. He remained silent despite cancer’s painful symptoms and concealed it for as long as he could and didn’t complain or ask for help.

Shikata ga nai (“Acceptance with Resignation”)

Another characteristic about my father is the “it can’t be helped” or “nothing can be done about it” attitude known as shikata ga nai (仕方がない).[11] The Japanese believe that when there are no alternatives, one’s fate and circumstance must be accepted, no matter how unfortunate. If something happens, which is beyond one’s ability to control or affect, such as a natural disaster, a predictable Japanese reaction is to say, “shikata ga nai.” With this expression, one recognizes that a problem exists, but one makes the best of the situation and gets on with doing what can be done. It describes the ability to maintain one’s dignity in the face of an unavoidable tragedy or injustice, mainly when the circumstances are beyond one’s control.

When my father began to experience the symptoms of stomach cancer, he hid it from everyone. He maintained gaman until he couldn’t hide the cancerous pain he was going through. His perceived lack of reaction to this adversity can be viewed as complacency. Still, I believe he wanted his dignity under the circumstances which was beyond his control.

Gisei (“Sacrifice”)

What I remember well about my father is that he made a lot of sacrifices, both personal and financial, for his family’s sake. He gave up one thing for another, many times. For example, he gave up going to the doctor or dentist because the money could be better used on his children, but it came at a cost, and it was to his own detriment. He suffered from several diseases – awful gum disease and lost most of his teeth; was a heavy smoker and had suffered from diabetes, which severely affected his eyesight; and, he had stomach cancer. Such sacrifice he accepted is known as gisei (犠牲).

My father surrendered things of value for the sake of a higher goal, his family. It was his selflessness and sacrifice that I sometimes find myself feeling conflicted about. I wished that he could’ve been a little selfish and didn’t sacrifice his own health and well-being, which he ultimately paid a high price with his life. I wished that he hadn’t been so complacent about his health and taken better care of himself; he might have well lived another 10-20 years.

COMPOSING THE JISEI

Jisei were customarily written or recited minutes before the author’s imminent death. But my father wrote his jisei five-years in advance of his death. As I learned, though, it wasn’t all that unusual to do that.

In Japan, it wasn’t unusual for the deceased to have consulted with a respected poet beforehand and sometimes well in advance of their death to help them finish the jisei. Sometimes a jisei could be rewritten after time passed. Changes often occurred in a person’s life, or after suffering from a prolonged illness, so it was acceptable as the person may have experienced phases of personal reflection. Of course, no one would mention the decease rewrote the jisei to avoid tarnishing the person’s legacy.

The fact that my father wrote his jisei years ahead of his death didn’t diminish his legacy. But I felt as if my bubble burst in a way and brought things back to reality. But I felt as if my bubble burst in a way and brought things back to reality. I conjured up glorified images of my father as to when and where he wrote his jisei, and the circumstances by which he felt duty-bound to write it. This was before learning that he wrote his jisei after his retirement. Thus, I initially speculated that there were two scenarios my father faced his humanity.

I thought that the most likely scenario would’ve been in the trenches and foxholes on the battlefields of Europe during World War II with the 442nd Regimental Combat Team (“442nd RCT” or “442nd”). The other likely scenario would’ve been while he was hospitalized at Kuakini Medical Center with stomach cancer. He was worried that he wouldn’t make it through surgery, so he summoned his brothers to communicate his dying wishes.

Nevertheless, neither scenario turned out to be the correct one that my father composed his jisei. I’ll share my thoughts on these two scenarios.

Military service during World War II

Like many Nisei, my father was small in physical stature – he was only 5-feet 2-inches tall and weighed 115-pounds – but that didn’t stop him from enlisting in the US Army infantry.[12] He spent more than two years of military service overseas. He took part in three (of five) battle campaigns with the 442nd RCT in the European and Mediterranean theater of operations, including the Rhineland Campaign-Vosges, Rhineland Campaign-Maritime Alps, and the Northern Apennines and Po Valley Campaigns.[13]

My father completed his military service having served a total of three-years, ten-months, and six-days before being honorably discharged on December 28, 1945. But he didn’t come out of it unscathed. During one battle, my father got hit by German machine-gun fire in his right leg, just above the knee.[14]

Miraculously, my father wasn’t killed in action, considering the high casualty rate experienced by the 442nd. He beat overwhelming odds and returned home safely. To think that 4,000 nisei men from Hawai’i and the mainland initially served with the 442nd, but the regiment had to be replaced at least three times is a sobering fact. In total, about 14,000 nisei men served, and about 70% either killed or wounded in action. In fact, the 442nd sustained so many casualties the regiment earned 9,486 Purple Hearts (many receiving double and triples) and 4,000 Bronze Stars.

When my father returned home from the war, he suffered from nightmares and would scream out at night in his sleep. The nightmares, he would say, were always about seeing his comrades dying under enemy gunfire or artillery bombardment. He also complained about how his knee would bother him whenever the weather got cold. The metal shell fragments still in his knee would expand and contract due to the change in the weather. I remember massaging his knee on many chilly evenings.

On a rare occasion, my father shared how the army would issue packs of cigarettes to every soldier. When he was in the foxhole, and the German artillery shells started exploding all around them, he started smoking to calm his nerves. This is the reason I thought for sure he wrote his jisei in a foxhole while awaiting the next battle

In his lifetime, like many Nisei who fought in the war, he didn’t speak about his war experiences. There was a high culture of not bragging or boasting about what they had done, humility, too. But, I’m sure the memories of the horrors of war kept my father silent as well.

Like his fellow 442nd comrades, my father faced death every day fighting on the battlefields of Italy and southern France. It’s hard to imagine how frightening it must’ve been out on the battlefields knowing he could get killed at any time. There must’ve been a countless number of times my father felt his time was coming, that is was going to get killed.

In feudal Japan, the samurai embraced the commonly used phrase: “to die before going into battle.” They were samurai, so they put themselves into a certain state-of-mind, allowing them to go into battle entirely without any fear of death before entering battle. They had their own death at the forefront of their mind, preferably “a good death” in combat. If a samurai went into each battle fearing death, he was sure to die. So learning to accept death as a plausible outcome of a fight, a samurai was able to entirely give himself to the battle, which often was the deciding factor leading to victory. Adopting this Zen belief that you’re already dead, there was nothing to fear; thus, it was a way to stay mentally focused now.

A famous swordsman in the early Sengoku period named Tsukahara Bokuden (1489-1571), wrote:

For the samurai to learn

There’s only one thing,

One last thing—

To face death unflinchingly.

That said, it was common for samurai to write their jisei before entering battles. They would ride into battle with their jisei tucked inside their armor, so in case they died, someone would carry it back to their families. Like the samurai, my father could’ve taken his jisei into each battle tucked away in the pocket of his army fatigues. I even imagined my father holding down in a damp foxhole or dugout on a freezing night with dense fog, mud, and heavy rain, writing his jisei. All the while anxiously waiting for the order to attack.

Whatever the circumstances, my father may have felt his “time to go” was coming up, and so he would’ve felt compelled to write his jisei. The great news, of course, was that his “time to go” never came up, and he returned home safely from the war.

Father’s Hospital Deathbed

Learning that my father had cancer came as quite a shock to the family. In hindsight, I can still recall the day I found out something was wrong with my father. It was a Saturday morning, and my judo club was having a huli-huli chicken sale.[15] By this time, my father had been retired and had already written his Living Will and his jisei. One of the judo club parents approached me and said that I should check up on my father because he didn’t look well. “Eh, Vince, you betta go check out your faddah. He no look so good,” the parent said (in Hawaiian Pidgin).[16] So I went to check up on him.

When I approached my father and asked him if he was okay, he became visibly upset and said, “Go away!” He said it with an annoying voice while brushing me off with his arm – motioning with swift backhand swipes toward me with his full arm several times. My father looked to be in pain; he had this grimace on his face as he tried to conceal it, but it was apparent that he wasn’t doing a good job of hiding it.

I can’t recollect how much time had passed from that Saturday to the time he was rushed to Kuakini Medical Center, where he was diagnosed with stomach cancer. It was apparent, though, that he had concealed his pain from everyone and must have been in agony for a long time.

While hospitalized, it was too late for the doctors to do anything to save his life. His cancer had spread too extensively throughout his body and to major organs. It was evident that he’d been suffering silently and suffering alone for some time. My father was someone who would put the needs of others ahead of his own needs. He made a lot of personal and financial sacrifices for the sake of his family, his children, even to his own detriment.

In one of Miyazawa Kenji’s (1896-1933) famous poems, Ame ni mo makezu (雨ニモマケズ, “Be Not Defeated by the Rain”), there’s a phrase that reads: “Count yourself last in everything. Put others before you.”[17] It was another of those times when my father put himself last that I found so heartbreaking. In his stoic way, my father bore the pain. He didn’t show it outwardly, keeping it hidden from the family for as long as he could until the pain became too severe and couldn’t hide it any longer. In that same poem by Miyazawa, another phrase reads: “Be not defeated by rain.” This phrase is the poem’s opening line, and it extols the virtues of gaman or enduring harsh conditions with good grace.

My father knew his life was ending soon. In fact, the morning before he died, my father woke up from his hospital bed and was very cheerful. He said he felt fine and was in unusually high spirits. He then said to the family members present that morning, “I don’t have any regrets.” The next day he passed.

As I mentioned, I speculated earlier that there were two scenarios for my father to compose his jisei. It was either on the battlefields of Europe while serving in the U.S. Army with the 442nd Regimental Combat Team or while hospitalized with cancer at Kuakini Medical Center. Of the two scenarios, it seemed more likely that he wrote his jisei while he was in the hospital, I thought. He knew his life was ending soon, and he had the time to write it. He even summoned his brothers to his bedside to discuss his final wishes, which included having his jiseirecited at his funeral service.

As it turned out, my father had been preparing for his death for years in advance. In hindsight, it was so typical of my father to think ahead for his death. He was a samurai at heart and true to his Buddhist upbringing, he accepted his fate and was prepared to die; he wasn’t afraid. “Death,” he stated in his Living Will, “is as much a reality as birth, growth, maturity and old age – it is certain I do not fear death…” Like the cherry blossoms petals falling when the time is right, he felt that when it was his time to die, he’d want to die naturally like a true samurai and without any regrets. This sentiment is reflected in his jiseiand how he lived life.

Sadly, reflecting on my father’s death, I thought how much I resented the very values that were instilled in him – gaman, shikata ga nai, and gisei. While his stoic Japanese spirit may be admired in many instances, I don’t always feel that way and resent it sometimes. Because of these values, my father endured silently and alone. If he had just spoken out sooner about this illness, he might have had a chance to live longer. If he had just gone to the doctor regularly and taken better care of himself, he might have found out about his cancer at an earlier stage. It may not have made much of a difference, but at least it would’ve shown that he put himself first, for once!

But, I suppose, “the time was right” for him to go. He died naturally like a true samurai and like the beautiful cherry blossom petals falling gently to earth, thus, fulfilling their purpose.

WHAT IS A JISEI?

The jisei has long been a core part of Japanese tradition. It dates back more than a thousand years to the earliest Japanese sources. But it didn’t become a popularized artform until the 19th century during the Meiji period (1868-1912).[18] Although the jisei isn’t practiced widely anymore, the Japanese still admire it as an essential part of their cultural heritage in close relation to traditional Buddhist and Shinto practices.

So, what is a jisei no ku or jisei?

A jisei no ku 辞世の句 or jisei 辞世 is a formal poetic message customarily written or recited near the time of one’s death. It literally means “passing away, death.” Zen Buddhist scholar D.T. Suzuki has called it a “parting-with-life verse.” One of the earliest jiseiwritten is recorded in AD 686 during the Asuka period (AD 538-710) by Prince Otsu (AD 663-686), a poet and the son of Emperor Tenmu.

Prince Otsu was a likely successor to his father to become the 41st emperor. But, after the emperor passed away, the prince was captured and accused of being a rebel because of Prince Kawashima’s betrayal. He was falsely charged with promoting a rebellion by Empress Jito to promote her own son, Prince Kusakabe, to the position of crown prince and forced to commit seppuku.

Monozutau

Iware no ike ni

naku kamo wo

kyo nomi mite ya

kumokakuri nan

Today, taking my last sight of the mallards

Prince Otsu (AD 663-686)

Crying on the pond of Iware

Must I vanish into the clouds!

Composing jisei was a custom that didn’t become popularized until the Meiji period (1868-1912). Westerners knew it popularly as “death poems” when they were exposed to it during the Pacific War of World War II (1941-1945). Japanese soldiers belonging to special attack squads of the Imperial Japanese Navy and Imperial Japanese Army called tokubetsu kōgeki tai 特別攻撃隊 or abbreviated as tokkōtai 特攻隊 would write jiseibefore their suicide missions.[19]

In the Japanese language, one of the meanings of the word shi 死 is “death,” so it’s rarely used directly about a person. Instead, the Japanese prefer to be indirect. They prefer the suggestion of death by using specific words associated with mortality. It includes words, such as: shinjū 心中 (lover’s suicide), junshi 殉死 (warrior’s death for his lord; dying a martyr), funshi 憤死 (suicide to express one’s indignation at a situation), kanshi 諫死 ( act of suicide to demonstrate one’s lord), senshi 戦死 (death in battle), sokotsushi 粗忽死 (suicide as a means for an offending samurai to make amends for his transgression)or rōshi 老死 (death from old age). Consequently, in Japan, these expressions of death closely associate with the life a person lived and to the circumstances of the person’s death, so the jisei is an extension of this idea.[20]

The basic idea of a jisei is that it offers an approach to someone facing death that can be expressed as a formal poetic message. A jisei was considered necessary as the final verse to capture a person’s last moments of reflection when they know death is at or near the final moment, so it can be obviously apparent and meaningful. Death is an inescapable part of life, and it’s the finality of life that gives it meaning. Consequently, it offered an essential and sincere insight into the nature of death and the value of life. In fact, a jisei tries to link the reader to the author’s mind at the final moment. By transcending a person’s thoughts, a jisei attempts to create an “Ah, now I see” moment. This idea isn’t surprising given the Japanese’s fascination with fleeting things that poetry may be used to capture a person’s final moments of reflection.

In fact, the word jisei, when written with the characters 自制, can also mean “self-examination” or “reflection.” It’s these last reflections and observations about a person’s death that can be expressed poetically and ceremoniously. Some jisei can be gloomy, while others are hopeful. The important thing is that the jisei reflect what’s on the mind of the person’s last days or moments before their death.

The critical thing about jisei is the profound sincerity presented in many of the poems. Emotions often range from peaceful, humorous, sarcastic, or even patriotic – we get a sense of a kind of enlightenment experienced by the poem’s author.

To the poem’s author, the jisei isn’t a legal Will, an elegy or a eulogy. It reflects the person’s “spiritual” legacy (a final testament or memorial, if you will) of that person’s life. It’s meant to be a parting gift of how he wished to be remembered after his death to loved ones left behind. The beauty of the jisei as a poetic form is its ability to communicate a lot while saying very little. It invites reflection on the brevity of both the jisei and life itself.

The thoughts expressed in a jisei are usually in a manner that’s direct, simple, and free of formal constraints. It allows one to articulate their ideas with a great deal of freedom in the poem’s elegant and natural form. It employs neutral emotions that adhere to the spiritual influences of Buddhist and Shinto teachings, which taps deeply into the human heart. It views life on Earth as being transient or fleeting. It isn’t so much that Buddhist philosophy preaches about death. More precisely, at its very core, Buddhism embraces transience and impermanence (mujō 無常) – all things that exist are transient or temporary; nothing lasts forever.

Accepting the certainty of death, before it occurs, is a crucial element of jisei; the poem comes directly from Zen’s acceptance of life, including the inevitability of death. With that said, one can be free once he can reconcile his relationship with fear and begin to enjoy life more fully when one stops worrying about dying.

Here’s a jisei in haiku (5-7-5) from the Buddhist monk Wagin, who died during the oshogatsu (New Year holiday) in 1758, at the age of 73:

kuse ni natte

nishi ogamikeri

hatsu ashita

It’s become a habit

bowing to the West

New Year’s dawn[21]

Wagin died two days after the first dawn of the New Year (January 3). Based on Shinto traditions, the Japanese bow to the rising sun to the East on the first morning of the New Year, it’s called hatsu ashita 初朝. The West is the direction for the land of the dead and the Buddhist paradise. As a Buddhist, Wagin was used to bowing to the West while turned his back on the rising sun. The Japanese have a saying that you are born Shinto and die Buddhist. This belief doesn’t mean you change your religion – if you’re born Japanese, you’re always Shinto, but you traditionally follow Buddhism.

Shinto ceremonies, on the one hand, tend to be more for the beginning of life, such as the ceremonies you take part in at certain ages as a child, or marriage, etc. On the other hand, a funeral, and celebrating the anniversaries of one’s relative’s death are always a Buddhist affair. Wagin suggested that he not bow to the rising sun to the East on New Year’s morning because he already belongs to the next world than to this one.

A good deal of jisei comes tinged with a playful sarcasm on life. On a winter morning in 1360, during the Muromachi period, the Zen master Kozan Ichiko (1283-1360) gathered together his students. He told them that, upon his death, they should bury his body, perform no ceremony, and hold no services in his memory. Sitting in the traditional Zen posture, he wrote the following:

Empty-handed I entered the world

Barefoot I leave it

My coming, my going

Two simple happenings

That got entangled.[22]

After he finished, Kozan gently put down his brush, and then died at age 77. He was still sitting upright.

Dream by Takuan Soho

(1573-1645) – Nomura Art

Museum, Kyoto, Japan

Other jisei weren’t poems at all. When the 17th century poet Sōhō Takuan (1573-1645) was asked to compose his jisei, he took a brush and just painted the kanji for “dream” (yume 夢), laid down his brush, and died.

There’s also the story of a Buddhist teacher named Shinsui. In 1746, in the Edo period, he was asked by his disciples to write his jisei during his final moments. Instead of writing a poem with words, with his last ounce of strength, he took a calligraphy brush and, with only a single brushstroke, painted just a circle and then cast the brush aside and died. In Japanese, the word for “circle” is ensō 円相; it isn’t a character, but a calligraphic symbol closely associated with Zen Buddhism.

From the beginning of Buddhist tradition, there was a symbolic relationship between the circle and the full moon, which was a symbol of enlightenment.

of ensō 円相 (Circle) symbol

The circle is one of the most important symbols of Zen Buddhism and has many meanings. It indicates the void and enlightenment. The circular form is a representation of the beginning and end of all things, nothing (zero) within it, or it could be from encompassing everything within it. Thus, the circle is the epitome of the Zen Buddhist state of mind where everything and nothing exists and exemplifies the completeness or the emptiness of the present moment.

The ensō symbol must be drawn in one swift stroke of the brush, revealing the spirit of the person at the time when the mind is free to let the body/spirit create simply. Zen Buddhists believe that only a person who is mentally and spiritually complete can draw a true ensō.

Symbols of death

The earliest jisei was an element of a full ceremonial seppuku (切腹) or ritual suicide by disembowelment. Still, it’s considered impolite to be explicit in mentioning a person’s own imminent death. It was deemed to be bad form and unrefined.[23] Instead, it was more acceptable to compose the jisei by using negative metaphorical references to nature to create specific and vivid images suggesting an inevitable death.

The Japanese love of nature and the seasons draw from this melancholy for the passing of things. The whole idea for many forms of Japanese art is to capture these fleeting moments of admiration at nature’s beauty. From hanami (cherry blossom viewing festival) to tsukimi (autumn moon-viewing festival), Japanese cultural and spiritual life is filled with a kind of worship for the fleeting beauty of nature.[24]

Early poems likened a person’s life to that of a wilting flower petal to represent the transitory world. Yet the flower also represented beauty. Japanese poetry regards the world through the change of seasons with longing and sorrow – hungry for the renewal of spring after fall and winter, and sadness that the cherry blossoms should last so short a time.

These images have changed over time. Later poems, especially those of the samurai class, added other images of nature, such as dewdrops that quickly evaporate at sunrise or a rainbow fading with the changing sunlight.

Thus, many jisei came filled with natural symbols, which trace to Zen Buddhist and Shinto spiritual beliefs, inferring the inevitability of death or the fleeting nature of life. Such natural symbols reference hinori 日の入り( a sunset), mangetsu 満月 (a full moon), clouds appearing in the westerly sky, hototogisu 時鳥 (the song of the cuckoo), higanbana 彼岸花 (red spider lily), chō 蝶 (butterfly), shiragiku 白菊 (white chrysanthemum), kōsetsu 降雪(snowfall) or falling cherry blossoms.[25]

Images of the seasons

These natural symbols of death also conjure up elements from nature to suggest images associated with a kigo (季語) or season of the poem’s author’s death. But, jiseidoesn’t always have to follow it.

The poet, Bako, who died in May 1751, wrote his jiseiin haiku form about the hototogisu, a type of cuckoo known for its song. He died in the spring, but the hototogisu is associated with summer.

furikaeru

tani no to mo nashi

hototogisu

Looking back at the valley

no more dwellings, only

the cuckoo cries[26]

My father’s jisei is another example. He died in the winter kigo, but the subject of his jisei is the cherry blossoms, which are associated with spring.

The Japanese like to make a big deal of the fact that they have four distinct seasons, and representation of and reference to the seasons has long been prominent in Japanese culture and poetry.[27] In Japan, the seasons change in subtle gradations, and this may have given rise to an aesthetic appreciation that finds beauty and poetry in each subtle change in nature. The expression semi-shigure 蝉時雨 means coming of mid-summer with “a continuous chorus of cicadas.”

The association of the seasons may be evident, although sometimes it can be very subtle. Fallen autumn leaves and dry leaves, for example, create an image associated with the winter kigo – just as kōyō 紅葉 (colored leaves) are a clear sign of the autumn kigo. The sight of aka-tonbo 赤蜻蛉 (red dragonflies) flying at sunset means autumn will be coming soon. Meanwhile, the higanbana 彼岸花 (red spider lily) signals the start of fall. The inekari 稲刈り or rice harvest is a sure sign of autumn. Farmers are getting rice paddies ready for planting, cherry blossoms, and cherry blossom viewing, and the new growth of fresh green leaves means shinryoku 新緑, “the fresh verdure [greenery] of spring,” are related to the spring kigo. A summer field (i.e., Hokkaido’s flower-covered fields), hanabi 花火 (fireworks), renge 蓮華 (lotus flower), himawari 向日葵 (sunflower) and semi 蝉, the sound of the cicada is connected to the summer kigo.

Less obvious was the moon, which is present all year round, is associated with the autumn kigo. But in autumn, when the days become shorter and the nights longer, it’s still warm enough to stay outdoors, and the night sky will more often be free of clouds, so people are more likely to notice the moon. The full moon can help rice farmers work after the sun goes down to harvest their crops, thus, the autumn harvest moon.

ISAMIS JISEI

As I mentioned previously, there’s a lot of speculation as to when and where my father was compelled to write his jisei.

Well, as it turned out, my father wrote his “parting-with-life verse” shortly after his retirement in preparation for his death. He drew-up a Living Will (in his own handwriting) to spell out his final wishes in case he could no longer make life-saving decisions for himself. He wanted to die naturally and honorably, like a true samurai.

In his Living Will, he included a poem, which, upon examination, turned out to be a jisei or death poem, and this is what he wrote:

Cherry blossoms fall

when the time is right

I too will fall

when it is time to go

The poem itself is aesthetically simple and focused. It’s rooted in Zen Buddhism, but it’s also elegant (fūryū). His words are heartfelt and profoundly sorrowful (mono no aware). The verse stirs up very intense feelings and, yet, its intimacy is profoundly moving. But, the idea of my father writing such verse left me dumbfounded. In all honesty, I didn’t think he was even capable of authoring such cultured poetry.

I can sense my father’s sincerity in the poem. It seems he chose each word carefully. Each word tied seamlessly together by each verse, and each line successfully conjuring up brilliant imagery of his death. The imagery was so aesthetically pleasing. Yet, it filled me with a sense of overpowering sorrowfulness that left me without words to be expressed.

Over time, I wanted to interpret the poem’s meaning, and I wondered what my father’s thoughts were at the instant he wrote it. The poem’s purpose didn’t immediately reveal itself to me – that is, until now.

My father’s jisei opened my eyes to something entirely unexpected from him. His jisei created a window openly revealing a side of him – divulging an intimate and vulnerable side – that was veiled from view, including from his own family and friends. It’s as if his impending death allowed him to free himself of any constraint from his pride (jiman 自慢) or shame (haji 恥). It stripped himself naked of every inhibition and burden from his dignity or faults he carried on his shoulders. Then he decided to bare it suddenly for everyone to see into like looking through a window. He revealed a view of death influenced by a Buddhist philosophical view that death comes as part of the natural course of life.

Professor Kishimoto Hideo (1903-1964) wrote in The Japanese Mind, “Death is not a mere end of life for the Japanese. It has been given a positive place in life. Facing death is one of the most important features of life. In that sense, it may well be said that for the Japanese, death is within life.”[28]As Kishimoto said, my father faced his death properly, and he did so in a manner that was so profoundly beautiful. His jiseihas a soulful depth that my heart was touched like I never imagined. Admittedly, it was a side of my father that was a stranger to me.

A sudden feeling of melancholy overcame me; I thought how sad it was not to have known this “other side” of my father. I’ve never witnessed him display his poetic talent, so I felt as though I missed out on this hidden talent, only to discover it after he was gone. My father’s jiseiinspired me to learn more about this ancient custom. By doing so, I hoped to gain a deeper understanding of my father. I hoped that by connecting the dots with the father, who was able to express his aesthetic sensibilities and sensitivities in writing this beautiful jisei, whom I didn’t know.

TANKA

With the assistance of Dr. Gladys Nakahara, a Japanese language instructor in the Department of East Asian Languages and Literature at the University of Hawai’i at Manoa, my father’s original jiseiwas adapted into the classical tanka form and then translated from English to Japanese rōmaji.

A jisei isn’t a poetic style per se. Still, its graceful and natural form, usually in a theme of transient emotions, represents more of an approach to one’s impending death. Most jisei written have historically been in the form of Japanese poetry, known as tanka 短歌. But jisei has also written in kanshi 漢詩 (poetry written in Chinese) or haiku 俳句.[29]

As a traditional form of lyric poetry, tanka is over twelve-hundred-years-old in Japan. It went as far back as the Asuka period (AD 538-710) in the 7thcentury; it’s even older than haiku. Tanka is considered an essential form of native poetry in Japanese culture.

After the capital moved from Heijō-kyō (present-day Nara) to Heian-kyō (present-day Kyōto) in AD 794, the popularity of writing poetry proliferated among the nobility. Tanka was the poetry of choice among the nobles in the Imperial court. They competed in tanka contests, and lyrical ability intanka often became a means of advancement to positions of power and prestige within the court.

Up until the 16th century, nearly all jiseiwritten took on the tanka form. The vital element of tanka is the beauty of life and nature and a feeling of longing. Tanka poems were gifts intended for loved ones, so they were written from the viewpoint of the author. Its suitability for directly expressing the author’s full range of feelings and emotions made it ideal for intimate communications. Tanka contains yojō 余情. It refers to the “suggestiveness” of the poem that’s felt beyond mere words. It’s like a lingering allure or lasting impression.

Tanka evoked or marked an occasion. It was essential for persons of culture to be able to compose beautiful poetry and even choose the most aesthetically pleasing and appropriate paper, ink, and symbolic attachment, such as a branch or a flower to go with it. No occasion was quite complete until a poem marked its finale.

As a “short poem,” tanka is a form of verse that doesn’t need to rhyme; it’s written in short lines that adhere to a specific mōra (モーラ) count – that is, the number of “phonetic sound units” per line.[30] In the Japanese language, the word mōra is known as haku (拍). Tanka poems are usually written as one continuous unpunctuated sentence. But it’s broken purposefully between all five lines that follow a 5-7-5-7-7 pattern for a total of 31-haku (mōrae モーラエ).

Line 1 – 5 haku

Line 2 – 7 haku

Line 3 – 5 haku

Line 4 – 7 haku

Line 5 – 7 haku

To fully appreciate tanka, it’s helpful to know that in each line of the verse the author tries to convey an image or idea. Although in the best tanka, the five lines often flow seamlessly together to create a single idea or thought.

It’s also helpful to know that tanka is usually made up of two poetic images. The upper phrase is taken from nature, and the lower phrase may precede, follow, or be interwoven into the first. It’s described by Yoel Hoffman as a “meditative complement to the nature image.” Hoffman compiled hundreds of Japanese jisei written by Zen monks and haiku poets into a book called Japanese Death Poems.[31] Tanka, according to Hoffman:

…produces a certain dreamlike effect, presenting images of reality without that definite quality of “realness” often possessed by photographs or drawings, as if the image proceeded directly from the mind of the dreamer. The tanka poet may be likened to a person holding two mirrors in his hands, one reflecting a scene from nature, the other reflecting himself as he holds the first mirror. The tanka thus provides a look at nature, but it regards the observer of nature as well.

The difference between tanka and haiku, according to Hoffman, is “…the mirror that reflects the poet. Haiku shattered the self-reflecting mirror, leaving in the hands of the poet only the mirror that reflects nature.”

The verses upper phrase of 5-7-5 haku (first three lines) refers to the kami-no-ku (上の句). In it, the poem’s author is trying to describe a natural object to create the image or idea that the author hoped to convey. In the lower phrase of 7-7 haku (last two lines), referred to as the shimo-no-ku (下の句), the author tries to suggest a viewpoint or personal response to that object. In-between, there’s a pivotal image (line three) that marks the transition from the description of the object to the response to the object.

Thus, my father’s jiseitried to convey an image of his death and life by exercising the Japanese symbolism of the “cherry blossoms.” It suggests that his thoughts were of the cherry blossoms in springtime, and their “falling” to represent both death and the fleeting nature of life. In his transition from the natural image to his personal response, he compared his life and how he wished to die like the falling petals. His response to the original image is reinforced by his reference to “time” – i.e., “when the time is right” and “when it is time to go.” It suggests that, now, in the face of certain death, he was ready in the same way as the cherry blossoms. He was facing the certainty of death, just like the petals fall naturally from its branches at just the right moment.

While my father was suffering from stomach cancer, he ultimately died of heart failure. As he stated in his Living Will, he requested he “not be kept alive by artificial means or heroic measures.” Further, he wrote, “Death is as much a reality as birth, growth, maturity and old age – it is the certainty I do not fear death.” My father must have made peace with his life – he even said, “I don’t have any regrets” – and he died as he had wanted!

Falling cherry blossoms

My father chose the cherry blossoms as his subject metaphor because he wanted to suggest a specific image of his death around the falling cherry blossoms’ profound symbolism. But, the imagery of the falling cherry blossoms has a deeper meaning beyond its pure aesthetic beauty and its seasonal reference. According to Emiko Ohnuki-Tierney, a Japanese American anthropologist, the cherry blossoms are a symbol of “the cycle of life, death, and rebirth, on the one hand, and of productive and reproductive powers, on the other,” throughout Japan’s history.[32]

On the one hand, the cherry blossoms draw a parallel to the Zen Buddhist idea of life being a great circle. This is about ensō, which symbolizes life as a circle because it’s like a constant loop. There are beginnings and an end to all life, which underlines the fact that all things must come to an end, and to the Japanese, the end (death) is equally as important as the beginning (birth). The idea of a circle is that the end of one existence isn’t necessarily the end of life altogether. Thus, when things die, it isn’t dead but reborn to begin another circle of life.

The Japanese people view their short lives as the fallen petals of the cherry blossoms. Unbelievably, someone calculated how fast a cherry blossom petal falls, and it’s believed to fall at five-centimeters (or two-inches) per second. The phrase “5 cm per second” comes from Shinkai Mokoto’s 2007 movie 5 CentimetersPer Second (Byōsoku Go Senchimeetoru, 秒速5センチメートル).[33] Shinkai’s film gives a realistic view of the struggles faced by many against time, space, people, and love. The petals being a metaphorical representation of humans, reminiscent of the slowness of life and how people often start together but slowly drift into their separate ways.

The drama staged by the life cycle of the cherry blossoms begins as an exquisitely beautiful and fragile flower. The trees are known for their short but brilliant blooming season. It all ends, the flowers gracefully falling to the earth at the height of its beauty and inevitable death. Then the blossoms are reborn and to start the process all over again the following spring, and so on. I can appreciate why my father chose the falling cherry blossom as his subject metaphor. He must’ve thought that when his time came to die, he would’ve wanted to “fall” naturally and gracefully, just like the beautiful cherry blossoms.

Hanafubuki

Arguably, the best part of hanami no kisetsu (花見の季節) or cherry blossom season comes at the end of the season. As the cherry blossom flowers reach their peak and are in full bloom, their petals begin to fall like a snowstorm. The Japanese call this hanafubuki 花吹雪, meaning “flower snowstorm,” and it marks the end of cherry blossom season. Hanafubuki is the Japanese word that describes the beautiful moment when the cherry blossom petals are blowing in the wind. At the end of the cherry blossom season, city pavements are covered like a pink carpet. Along with watching the petals fall from the trees at season’s end, the ground is left covered by a pink carpet of petals. It’s possibly the most beautiful sight of hanami, but it’s also a sorrowful occasion for the dying flowers.

During the Heian period, the priest, Saigyo Hoshi (1118-1190), wrote many poems expressing the tension he felt between renunciatory Buddhist ideals and his love of natural beauty. He wrote the following verse:

願わくは花の下にて春死なむ

その如月の望月のころ

negawaku wa hana no shita nite haru shinamu

sono kisaragi no mochizuki no koro

Let me die in spring under the blossoms trees,

let it be around the full moon of Kisaragi [February] month.[34]

Another poet during the Edo period, Kobayashi Issa (1763-1828), known as one of the haiku masters in Japan, along with Basho, Buson, and Shiki, composed the following haiku:

死に仕度

致せ致せと

桜哉

shini shitaku

itaseitase to

sakura kana

Cherry blossoms

press me to

prepare to die.[35]

Productive and Reproductive Powers

On the other hand, the cherry blossoms have been a symbol for predicting successful rice harvests in autumn. The cherry blossoms are revered with productive and rebirth powers. They are believed to represent the mountain deity (Yama-no-kami) that transformed into the deity of the rice paddies (Ta-no-kami) in Japanese folk religions. Cherry blossom trees signify agricultural production and reproduction. Every spring, the mountain god would come down from the mountains to the rice paddy fields. He would come down riding on the falling cherry blossom petals and transform into the rice paddy god, which is a critical crop for Japanese agriculture and production. It was during this time peasant farmers traveled to the mountains to worship the trees, which were considered sacred since they carried the soul of the mountain deity down to humans in the villages.

The cherry trees are connected to the rice-growing cycle. Since ancient times, the Japanese system of sustainable wet-rice farming was very sophisticated.[36] The rice-growing cycle begins around the time the long winter ends. When the cherry blossom trees start to bloom in spring, it was a sign used by farmers to determine when to begin sowing the rice seedlings. In the early summer, they transplant the seedlings to wet paddies. It’s cultivated under the summer sun and produces grain, and this grain gets harvested in the autumn. This cycle has been repeated in the same way for many centuries, according to the changing of the seasons.[37] This attitude is why the sequence of the seasons are still intimately connected with contemporary Japanese life.

Many festivals are held throughout Japan, celebrating the deity of the rice paddy between spring and autumn in line with the various stages of the rice-growing process. But they are especially notable around the time of spring transplanting, while other rituals are held at harvest time. For example, during the spring, there are ceremonies called saori (greeting the rice-field kami) and sanaburi (or sanoburi, “sending off the rice-field kami”). Meanwhile, during the autumn, there are ceremonies called i-no-ko (“child of the boar”) and tōkan’ya (“tenth night”).

The cycle of spring and autumn festivals celebrating the rice paddy deity is seen throughout the country and are linked to Japanese folklore between the rice paddy deity and the mountain deity in those two seasons. Namely, in spring, it’s believed that the mountain deity descends from the mountain to the village, becoming the deity of the rice paddy. In fall, the rice paddy deity leaves the field and returns to the foothills, where it transforms back into the mountain deity.

Ideal Death

Cherry blossoms also exemplified the noble character of the “Japanese soul” – men who don’t fear death. As seppuku became a crucial part of the samurai’s Bushido code, the samurai identified with the cherry blossoms. Its petals fell at its most beautiful moment, which became the “ideal death.” The daimyō Asano Naganori (1675-1701) of the Aiko domain in Harima Province (in the southwestern part of present-day Hyōgo Prefecture) captured this sentiment in his jiseibefore being ordered to commit seppuku for drawing his sword against Lord Kira in Edo Castle. It was strictly forbidden to draw a sword in Edo Castle and a capital offense.[38]

Lord Asano wrote his jisei, expressing his regret at being cut down in the flower of his youth; he was 34 years old:

Sadder than blossoms swept off by the wind,

a life torn away in the fullness of spring.[39]

Another interpretation of Lord Asano’s jiseiis from Japanese film director and screenwriter, Mizoguchi Kenji , who is known for his 1941 film, The 47 Ronin:

kaze sasou hana yori mo

nao ware ha mata

haru no nagori wo

ika ni toyasen

More than the cherry blossoms,

Inviting a wind to blow them away,

I am wondering what to do,

With the remaining springtime.[40]

In the Hagakure, an 18th-century book which stated that bushido was to be found in death. An excellent example of the connection between samurai and death can be found in the opening chapter itself: “The Way of the Samurai is found in death. When it comes to death, there is only the quick choice of death.”[41]

In the 2003 movie The Last Samurai, in one of the conversations Katsumoto has with Algren, Katsumoto tries to explain the concept of Bushido: “Like these [cherry] blossoms, we are all dying. To know life in every breath, in every cup of tea, in every life that we take – the way of the warrior…That is bushido.”[42]

Katsumoto wanted Algren to understand that the way a samurai viewed his own death was considered significant. A samurai doesn’t fear death because they know that they have done their duty for their country and realize they take lives every day. They understand that life is not infinite, and they lead lives that allow them to feel a sense of accomplishment. Their entire lives, they’re training for death and know that in battle they could die, so they’re ready for it, and have accepted it.

Sacrifice of Japanese Soldiers

Cherry trees also reflected the sacrifice of the Japanese soldiers in service to the Empire of Japan during wars from 1867-1951. It was considered an honor to die on the battlefield like scattered cherry blossom petals. Each fallen cherry blossom petal symbolizes each fallen Japanese soldier. Death on the battlefield was deemed to be honorable. Japanese artists often wrote poems and painted images of it, comparing it to the delicate beauty of the flowers falling off the trees.

During the Meiji Restoration (1868-1912), Emperor Meiji reclaimed all the governing authority from the position of the shōgun, and by asserting the Emperor held supreme power, he established the Empire of Japan. As a result, the samurai lost their social status and privileges. After universal conscription, a newly created Japanese imperial army bestowed upon its soldiers with the Japanese spirit or soul. It was an exclusive spiritual property of the Japanese that endowed young men with a noble character, which allowed them to face death without fear. The soldiers were told: “You shall die like beautiful falling cherry petals for the emperor.” This phrase was only one part of the Emperor’s imperial nationalist goals and guided Japanese colonial efforts.

Cherry trees console the souls of soldiers at Yasukuni Shrine, a Shinto shrine in Chiyoda, Tōkyō, founded by Emperor Meiji. It commemorates all who had died in service to the Empire of Japan, from the Meiji Restoration of 1868 until the Allied Occupation renamed the new nation-state as Japan in 1947. The shrine’s mission has been expanded over the years to include those who died in wars involving Japan spanning the entire Meiji and Taisho (1912-1926) periods, and lesser part of the Showa Period (1926-1989).

Yasukuni Shrine, however, is a hugely controversial shrine due to its position as a memorial to those who died in World War II. Emperor Meiji chose the name “Yasukuni” because it means “preserving the peace of the nation.” It could be seen to exist even though the shrine’s first association with war and reminds people to consider the value of peace.

The cherry blossoms had given the World War II select suicide attack units, known as tokkōtai (特攻隊), courage on their one-way missions. The tokkōtai included the more well-known kamikaze (神風) pilots, suicide frogmen, suicide boats, and submarines. Following several military losses and nearing defeat in the war, conventional warfare was no longer an option for Japan to protect its homeland and the Japanese spirit. Japanese naval vice admiral Onishi Takajiro (1891-1945) launched kamikaze operations in the Philippines in October 1944 as a last-ditch effort. Kamikaze pilots affixed cherry blossom branches to their uniforms. They painted cherry blossoms on the sides of the plane before embarking on their (one-way) missions. It represented the sacrifice pilots were making for their country to “die like beautiful falling cherry petals for the emperor.”

The cherry blossoms became a symbol of soldiers, especially the tokkōtai soldiers, by a military song called “Dōki no Sakura” 同期の桜. Soldiers of the same corps called themselves “dōki no sakura” (Cherry blossoms of the same class/period). It suggested that they were happy to fall and die for their country and their loved ones. Thousands of kamikaze pilots ended up flying their planes to their deaths. People also believed that these flowers were the souls of the soldiers who lost their lives in battle.

The poet Tamura Ryūichi (1923-1998) once shared a story in an interview with a survivor of the battleship Yamato. The survivor told him that the ship left Kure Naval Base (near Hiroshima) in the spring, and as fate would have it, it turned out to be the Yamato’s last mission.

“He saw full bloom of cherry blossoms from town to town and thought what a beautiful country I belong to! For this beautiful country, I can sacrifice my life and pray that the younger generation build a peaceful country.” Tamura noted that this was the typical Japanese philosophy; this soldier was going to die for the flower.[43]

Thus, the symbolism of the cherry blossoms comes from the belief that life is short and beautiful, like the cherry blossom flower’s lifespan. Therefore, it’s not surprising that the cherry blossoms evoke a strong emotional connection within the soul of Japanese people.

Adapting my father’sjiseiinto tanka form

My father wrote his jiseiin English using four lines and 20-syllables, which didn’t follow the classical Japanese tanka form of five lines and 31-haku. Dr. Nakahara took the liberty to modify my father’s original jisei to be consistent with the tanka form by breaking up the fourth line “I too will fall” into two phrases as follows:

Original Jisei

Cherry blossoms fall

when the time is right

I too will fall

when it is time to go

Jisei in tanka form

Cherry blossoms fall

when the time is right

I too

will fall

when it is time to go

Next, Dr. Nakahara translated the jiseifrom English to Japanese rōmaji. In doing so, she was mindful of the fact that there are some vast differences between the English and Japanese languages.

Syllable count versus mōra count

The Japanese syllabic writing system of kana (仮名) is based on mōra (モーラ) or haku (拍), referring to phonetic units of sound. Each kana character corresponds to one haku in the Japanese language.[44] When text, such as my father’s jisei, is translated into hiragana (平仮名), counting kana is the same as counting haku. While haku are very similar to syllables, there are subtle distinctions between the English syllable count and the Japanese haku count. For example, Japanese forms of poetry, such as tanka (31-haku in a 5-7-5-7-7 pattern) and haiku (17-haku in 5-7-5) poetry, aren’t based on syllable counts, but on haku count.[45]

Long vowel such as aa, ii, ou, or ei count as one syllable, but counts as two haku (a-a ああ; i-i いい; o-o おお; e-e ええ). In cases where hiragana is represented by a pair of symbols such as kyo きょ, each pair counts as one haku. For example, the names Tōkyō, Ōsaka, Niigata, and Nagasaki count as two, three, three, and four syllables, respectively, but each name has four haku. In hiragana, the four haku is represented by four kana: to/u/kyo/u とうきょう; ni/i/ga/ta にいがた; o/o/sa/ka おおさか and na/ga/sa/ki ながさき.[46]

Double consonants, such as pp and tt count as two haku. For example, the word oppai (breasts) count as two syllables but count as four haku. In hiragana, the four haku represents four kana: o/p/pa/i おっぱい.[47]

A syllabic n (ん) counts as one haku. For example, the word for red bean paste in Japanese is an and counts as one syllable but counts as two haku. In hiragana, the two haku for an represents two kanji: a/n (あん). Take, for example, the words hanbun (half) and kankei (relationship). Both hanban and kankei count as two syllables, but both count as four haku. In hiragana, the four haku of hanbun and kankei represents four kana: ha/n/bu/n はんぶんand ka/n/ke/e かんけい, respectively.

Similarly, the Japanese name for Japan 日本 has two different pronunciations, Nihon and Nippon. Both count as two-syllable words, but Nihon counts as three haku, and Nippon is four haku. In hiragana, the three haku of Nihon and four haku of Nippon are represented by three and four kana, respectively: ni/ho/n にほん and ni/p/po/n にっぽん.[48]

Next, recognizing the differences between the English syllable count and Japanese haku count, Dr. Nakahara carefully and caringly translated the jisei from English to Japanese rōmaji following the 5-7-5-7-7 haku pattern.

toki kureba 5-haku

sakura chiri yuku 7-haku

ware mo mata 5-haku

toki ga jukuseba 7-haku

chiru yokan suru 7-haku

Once Dr. Nakahara translated the jisei into Japanese rōmaji, I attempted to transliterate it to hiragana.

とき くれば 5-haku

さくら ちり ゆく 7-haku

われ も また 5-haku

とき が じゅくせば 7-haku

ちるよかん する 7-haku

Transliteration from rōmaji to kanji

Once in hiragana, I took the next step and transliterated the jisei to kanji. Dr. Nakahara and my Japanese language teacher, Yuko Hanamure, or just “Yuko-sensei” of Smile Nihongo Academy (smilenihongo), reviewed it for accuracy.[49]

Of course, transliterating the jisei from rōmaji to kanji can obscure wordplay. In the Japanese language, a single word can be pronounced the same and have several different meanings based on the kanji used to write it and the context to be used. Similarly, individual kanji may be used to write one or more different words. Thus, the same kanji may be pronounced in different ways and have several different meanings.

Deciding which kanji to use depends on recognizing which word it represents. It can be determined from the specific context, its intended meaning, whether the character occurs as part of a compound word or an independent word, and sometimes its location within a sentence. It’s what makes the Japanese language so complicated to learn. Many poets use this to their advantage to build multiple layers of meaning, something English translations lose out on this aspect of the Japanese language.

To understand what was in my father’s mind at the time he wrote his jisei, I very carefully selected the appropriate characters to reflect my father’s thoughts. It cannot be done using a phonetic alphabet like hiragana.

| Tanka | Hiragana | Haku | Kanji |

| toki kureba | とき くれば | 5-haku | 時来れば |

| sakura chiri yuku | さくら ちり ゆく | 7-haku | 桜散りゆく |

| ware mo mata | われ も また | 5-haku | 我もまた |

| toki ga jukuseba | とき が じゅくせば | 7-haku | 時が熟せば |

| chiru yokan suru | ちるよかん する | 7-haku | 散る予感する |

The upper phrase or kami-no-ku (上の句) of the tanka “Cherry blossoms fall when the time is right” (lines 1-2) describes the natural object. The author hopes to convey the image or idea. The natural object my father chose for his subject was the sakura 桜 or cherry blossoms.

Line 1 (“…when the time is right” / “…toki kureba”)

The first line of the jisei, when written in Japanese hiragana, begins with “…when the time is right,” which translates into Japanese rōmaji as toki kureba. Both the syllable count and haku count is five. The five kana represents the five haku in hiragana: ときくれば (to/ki/ku/re/ba).

- Tokiとき/時: The word toki means “time;” it roughly translates as “at the time of” and is used to express time when some states or actions exist or occur. Toki connects two sentences and expresses the time when the state or action described in the main sentence takes place. Interestingly, the character for toki or 時 is the same used for ji, which means “hour” or “o’clock” (e.g., 2-ji or 2 o’clock). When the word “time” is used as a noun, the word jikan 時間 is used, but it shouldn’t be confused with the use of toki. It can be used as a conditional (e.g., “if it rains, then it’s raining”), but, in the context of my father’s jisei, it’s more likely to be used as an actual (e.g., “when it rains, it pours”). Regarding haku count, toki counts as two haku. In hiragana, the haku is represented by two kana as とき (to/ki).

- Kureba くれば/来れば: The word kureba comes from the word kuru くる, which means “to come.” The word kuru is a verb and belongs to an irregular verb group or –ba/-eba form; it’s a conditional, meaning it’s usually used in hypothetical “if/when” situations. As a conditional form, the -ba/-eba form is characterized by the final -u in kuru becoming -eba. Thus, in the context of my father’s jisei, the use of the -ba/-eba form is intended to refer to “when something happens,” as in “when the time is right, the cherry blossoms fall.” Regarding the haku count, kureba counts as three haku. In hiragana, the haku represents three kana as くれば (ku/re/ba).

Second line (“Cherry blossoms fall” / “sakura chiri yuku”)

The second line of the tanka is: “Cherry blossoms fall…” which translates into Japanese rōmaji as sakura chiri yuku. For line two, the syllable count is five, but the haku count is seven. In hiragana, the haku is represented by seven kana as さくちりゆく(sa/ku/ra/chi/ri/yu).

- Sakura さくら/ 桜: As a noun, the word sakura means “cherry tree” or “cherry blossom.” Regarding the haku count, sakura counts as three haka. In hiragana, the haku represents three kana: さくら(sa/ku/ra).

In tanka, the treatment of the subject is so necessary as it reflects an image of nature to express a thought or feeling. The cherry blossom flower is a representative of beauty and linked with spring in Japan; it’s a season often connected with youth and innocence. Perhaps when my father wrote hisjisei, he was reflecting on his days as a young boy growing up in the sugar plantation town of Pa’auilo on Hawai’i Island. He must’ve had many fond and happy memories of an innocent time in his life.

But my father used the cherry blossom flower as his neutral subject metaphor for his jisei. He made specific reference to falling cherry blossoms, which are a resonant symbol in Japan and conjures up images of decline, waning, regret, loss, and something coming to an end. Interestingly, my father chose a flower. In Japan, the samurai had a special appreciation for art and beauty. They treasured flowers and considered them a part of the life of a warrior. It was also a symbol of the fleetingness of their existence. Death wasn’t explicitly referred to by a corpse but likened to wilting or falling flower petals.

But the Japanese don’t avert their eyes from the departing blossoms. Instead, they watch the end of the season as avidly as they welcomed its onset, with a sense of gentle mourning. An air of nostalgic reminiscence and profound melancholy must’ve surrounded my father as he reflected on his death. With that said, the falling cherry blossom was the perfect subject metaphor my father could’ve chosen to create the image of how he wanted to convey his emotions at the time.

- Chiriちり/ 散り: The next word chiri comes from chiru 散る, which means “to fall” (like falling blossoms or falling leaves). It can also mean “to die” as in to die “a noble death in battle.” Regarding the mōra count, chiri counts as two. In hiragana, the haku represented two kana: ちり (chi/ri).

My father used the symbolism of the falling cherry blossom petals to create an image of his death. That image is of the cherry blossom petals falling gracefully to the earth at the height of its beauty and to its inevitable demise. He must’ve thought that when his time came to die, he would’ve wanted to “fall” naturally just like the beautiful cherry blossoms and die an honorable death like a samurai. Yuku ゆく/ 行く: The word yuku means “to die” or “to pass away.” Regarding haku count, yuku counts as two. In hiragana, the haku represents two kana as ゆく (yu-ku).

Third line (“I too” / “ware mo mata”)

The third line marks the transition from the “upper phrase” of the tanka to the “lower phrase” or shimo-no-ku (下の句). The description of the natural object (cherry blossoms or trees) transitions to my father’s response to the natural object. The phrase in line 3, “I too,” is translated into Japaneserōmaji as ware mo mata. For line three, the syllable count is two, but the haku count is five. In hiragana, the haku represents five kan as われもまた(wa/re/mo/ma/ta).

- Ware われ/ 我: The word ware means “I” or “me.” Concerning the haku count, the ware counts as two haku. In hiragana, the haku represents two kana as われ (wa/re).

- Mo も: The word mo is a particle that means “too,” “as well,” and “also.” Japanese particles are in hiragana, so mo is written as も. Regarding hakucount, the word mo counts as one. In hiragana, the haku represents one kana as も (mo).

- Mata また: The word mata means “bye” or “see you.” In the context of this poem, mata is used when saying goodbye to someone that has died or passed away. Regarding haku count, mata counts as two haku. In hiragana, the haku is represented by two kana as また (ma-ta).

Fourth line (“when it is time to go” / “toki ga jukuseba”)

The lower phrase of the tanka (“when it is time to go”) suggests my father’s viewpoint or his personal response to the falling cherry blossoms in the upper phase. The lower phrase translates into Japanese rōmaji as toki ga jukuseba. For line four, the syllable count is six, but the haku count is seven. In hiragana, the haku represents seven kana as ときがじゅくせば (to/ki/ga/ju/ku/se/ba).

- Toki とき/ 時: As in the first line, the word toki means “time.” It translates as “at the time of.” Toki counts as two haku. In hiragana, the two hakuequates to two kana: とき (to/ki).

- Ga が: The word ga is a particle and marks the subject of a sentence, and it means “but; however; still; and.” Japanese particles are in hiragana, soga, which counts as one haku. In hiragana, the one haku equates to one kana: が (ga).

Jukusebaじゅくせば/ 熟せば: The word jukuseba comes from jukusu (熟す), which means “to ripen; to mature; to become ripe” as to imply that “it’s the right time (to act).” The -ba/-eba form is a conditional form and characterized by the final -u in jukusu becoming -eba (jukuseba) for all verbs. In conditionals, the emphasis rests more on the condition than with the result – e.g., “when it is time, it’s the right time (to act).” Jukuseba has a haku count of four. In hiragana, the haku represents four kana: じゅくせば (ju/ku/se/ba).

Fifth line (“will fall” / “chiru yokan suru”)

Finally, the fifth line “will fall” is translated into Japanese rōmaji as chiru yukan suru. Then, word chiru repeats from the second line, except its meaning here is in the future tense. For line five, the syllable count is two, but the haku count is seven. In hiragana, the seven haku equates to seven kana: ちるよかんする (chi/ru/yo/ka/n/su/ru).

- Chiru ちる/ 散る: The next word is chiru, and it means within the context of the poem as either “to fall” (like falling blossoms or falling leaves) or “to die.” Chiru counts as two haku. In hiragana, the haku equates to two kana: ちる (ch/-ru).

- yokan よかん/ 予感: The word yokan means “a feeling” or “a hunch.” Yokan counts as three haku. In hiragana, the haku equates to three kana: よかん (yo/ka/n).

- Suru する: The word suru means “to do.” In the context of my father’s jisei, suru is used to say, “when the time is right.” Suru counts as two haku. Inhiragana, the haku equates to two kana: する (su/ru).

Dr. Nakahara used the phrase yokan suru, which means “I have a feeling” or “I have a hunch.” Dr. Nakahara’s choice of this phrase is very appropriate. It infers that my father was having a sense or feeling that his life would end soon (albeit five years) after he wrote the jisei. But it showed my father was already preparing for his death and anticipating his “time to go” (to die). When he chose the falling cherry blossoms as his subject metaphor, he had already envisioned how he wanted to die. He wanted to die naturally like the cherry blossoms petals falling gracefully to the earth.